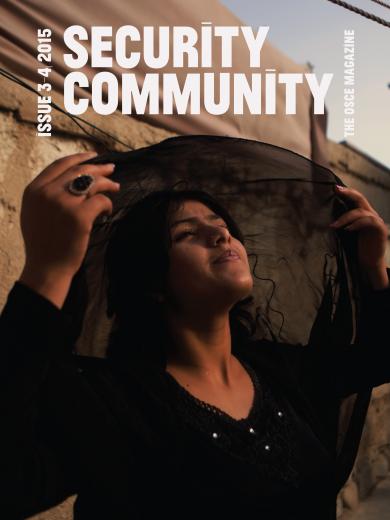

Afghanistan's Women: Keeping the Peace

In today’s Afghanistan, women are playing an ever greater role in the task of building the country’s security. This is part of the new Afghanistan, but there is continuity, too. Already a hundred years ago, the Afghan constitution guaranteed women a place in public life. Two prominent Afghan women, Shukria Barakzai, who took part in drafting the new constitution in 2003 and chaired the parliamentary defence committee under the previous government, and Hasina Safi, who directs the Afghan Women’s Network, talk about milestones and challenges in defending that right.

"They’re doing a wonderful job"

Shukria Barakzai

Is there a history of women working for security in Afghanistan?

Throughout the ages, Afghanistan has known strong and powerful women: Razia Sultan ruled in the 13th century, the empress Goharshad Begum in the 14th. In 1880, the heroine Malalai rallied Afghan forces to fight for freedom from British rule, leading to victory in the Battle of Maiwand. That is a part of our history no one can deny.

A hundred years ago, when our first constitution was being developed, five women took part in the drafting. There were female elected members of parliament from the time it started to function. We had women working in industry. Education was very important; many would go abroad to study, for instance to Turkey. Then, suddenly, everything changed. After the Soviet occupation, the ideas of Islamists and mujahidin came to the fore. The culture of violence replaced the culture of peace. Our country went through difficult times.

The presence of the international community from late 2001 brought a ray of sunlight, new hope. At the International Conference on Afghanistan in Bonn, it was agreed to name two women to the cabinet of the new government, to the posts of Vice-chair of Woman's Affairs and Minister of Public Health. The constitution, which we adopted in 2003, ensures fundamental rights for men and for women and includes provisions for positive discrimination in favour of women. It reserves a minimum of 25 per cent of seats in the parliament for women candidates. It ensures women’s participation in different sectors, including the security sector. Article 55 clearly states that Afghan citizens, men and women, are responsible for the security of the country.

What was your experience as a woman chairing Afghanistan’s parliamentary defense committee?

The defense committee is one of the most important committees, second only to foreign relations. It has a direct connection to the work of the Afghan National Security Force. When I chose to go to the defense committee after five years working in human rights, civil society and women’s affairs, the idea was a nightmare for me. But I knew that United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 on women peace and security would never become reality if women were not engaged in the security sector and the peace process. So therefore I decided to be there, to ensure that women’s issues would be considered.

How did I manage my role as chairwoman? In a one-year period, we had two four-and-a-half-month terms. In the first, I sat in the committee and asked the entire security institution to come and brief us. We were the ones taking notes: about what they were doing, about their strategy, their national conferences and about the transition – because in that year the transition started, the transfer of the responsibility for security from the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) to the Afghan National Security Force. We tried to increase their numbers; we tried to support them; we tried to fight corruption.

In the second part of the year, I travelled to the military bases, which is very, very unusual. For most of the men, it was the first time they were saluting a women in a military base. In fact, it was the first time a government official was coming and seeing how they were doing. I tried to be deeply engaged, starting with their working conditions. Were they eating? Were they sleeping? What medical supplies were they getting? Were they receiving their salaries? How were they fighting? How were they organizing themselves? Where was their air support? Where was their ground support? It was like a college education for me – not only for me, for them, too.

Sleeping on the military bases, spending time there, going to the areas where fighting was ongoing, travelling in military helicopters with open doors and gunmen, all of this was very new for me and I was always thinking to myself: “yes, it’s really me. I’ve always been against these guns and look at me now.”

How were you able to support women in the security sector?

It was an ongoing process. I went to see women who were working in the Afghan National Security Force and in the police force as well. I checked with them about their salaries and they told me about their situation, including about cases of sexual abuse. I remember once, at a conference, advising the Minister of the Interior, “if any man acts disrespectfully towards a policewoman, you need to punish him in front of everybody; it should be a lesson for the others to stop.” Unfortunately, abuse is a reality, it’s happening, whether we like it or not.

As a rule, women and men are supposed to receive equal salaries, but we decided that women in the security sector should get a higher salary, so that they do not have to work as many nightshifts and can stay with their children. We also worked on providing kindergartens and collective housing for policewomen. Unfortunately, in our culture, it is still unpleasant for kids to have mothers in uniform: neighbours tease them because of their mother wearing men’s clothes and such things.

We need to work on changing this attitude, on cultivating the image of women in the security sector as a role model. We already have women who are military pilots. They’re working with the Afghan National Security Force. Not only as officers. They’re going for special operations, also for night operations, which are very important. They’re abseiling from helicopters, like in Hollywood movies. They’re well trained and they’re doing a wonderful job.

“Women are essential to nation-building”

Hasina Safi

How has the Afghan Women’s Network (AWN), which you direct, helped women to participate in the reconciliation process in Afghanistan?

The AWN has been involved in peace-making efforts since its establishment. In fact, we started it back in 1995 because of the conflict situation and the more complicated situation of women in Afghanistan at that time.

Women have an important role to play. Considering that the family is the foundation of a society, and the energy of women a mobilizing force within the family, it is clear that women are essential, not only to the process of reconciliation, but also to stability and nation-building.

Our first success in the fight for involvement in the peace process was in 2010, at the first Peace Jirga, a national consultation on bringing peace to Afghanistan. It was the first national Jirga in which women were allowed to be part of the reconciliation process, as is our right set out in the national constitution. Four women were invited to take part. When we saw that only four were invited, we took the matter to the president, referring to our constitution and to United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1325 on women, peace and security. After a lot of advocacy, we managed to get the number of women up to 240 out of more than 1600 delegates.

Since the establishment of the Afghanistan High Peace Council under the Afghanistan Peace and Reintegration Programme, we have been working with women who are members of the Provincial Peace Councils. We were working in Kabul, but realized that women in the provinces lacked opportunities. So we started capacity-building programmes for them. At the beginning they were hesitant and lacked confidence. But today, some go out and talk to women and their families and even to members of armed groups. They are women who can reason. They are demonstrating their capability and showing that they are active members of the reconciliation process.

How important is UNSCR 1325 for Afghanistan?

It is a decade and a half since the UN Security Council adopted UNSCR 1325. Ten years ago, its meaning was not very clear to top decision makers in Afghanistan. It was just a number. But gradually, with more awareness-raising, co-ordinated by different UN member states and relevant partners, it has been recognized as an important document aimed at involving women in conflict zones in the peace and reconciliation process.

In June of this year, Afghanistan launched its National Action Plan on UNSCR 1325. We worked for two years on its development. I sat in the advisory committee and the AWN was also represented in the technical committee. In addition, we worked with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to define what UNSCR 1325 means for women in Afghanistan: what they want from the peace; what challenges they are facing. We organized consultations with women at the grass-roots level all over Afghanistan and provided the Ministry with ideas and recommendations for the National Action Plan on behalf of civil society.

We have been preparing annual shadow reports similar to the reports submitted by countries that have already ratified UNSCR 1325. The reports are based on the four pillars of UNSCR 1325: prevention, protection, participation and relief and recovery. They monitor what is happening on the ground – for example, how women have been promoted – and match this against the resolution’s implementation indicators.

Can you describe your efforts to bring more female politicians into government and the security sector?

As I mentioned above, our constitution has several articles supporting the participation of women in public life. At first, we focused our efforts on having women included in decision-making. Today we are fighting for an increase in numbers. Currently, 68 women are represented in the parliament. We have been advocating for women in the cabinet as well, demanding the inclusion of at least eight women. It has not happened yet; currently we have four.

There are women in the security forces, but we have to think in terms of quality opportunities. Women in the security sector face a lot of challenges. Many of them are widows, and it is they who provide for their families. When problems arise in the workplace, they sometimes keep silent for fear of losing their job. Opportunities are not given equally to men and women, regarding salaries or privileges, for instance. There are cases where male officers are provided with a vehicle and bodyguard, while female officers might not even get money to cover their transport costs. The widows among them need someone to look after their children. Are they provided with facilities like kindergartens? Usually not. We also hear that in some conservative areas, people refuse to rent their houses to female police officers, saying that they are not “good women”. These are some of the difficulties women still face.

Saule Mukhametrakhimova, Media Officer in the Communication and Media Relations Section, OSCE Secretariat, spoke with Hasina Safi.

UNSCR 1325 on women, peace and security

The United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1325 is the first of eight resolutions on women, peace and security. The resolution recognizes that women and men have different experiences of conflict and war and that both need to be taken into account in order to reach sustainable peace and stability. The resolution calls for the inclusion of women in four areas: participation of women in peace processes, protection of women in war and peace, prevention of conflicts and prosecution of perpetrators of sexual and gender-based violence and the inclusion of women in post-conflict reconstruction efforts.

The OSCE recognizes gender equality as essential to fostering peace, sustaining democracy and driving economic development. Building on UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on women, peace and security, it has developed its own policy framework to ensure that its comprehensive security efforts are inclusive of both men and women. Afghanistan has been an OSCE Partner for Co-operation since 2003. Here are some ways the OSCE and Afghanistan have worked together to bring the perspective of women to bear on security-related activities.

The OSCE, Gender Equality and Afghanistan

Peacebuilding

The OSCE Secretariat’s Gender Section promotes women’s leadership in peacebuilding. To raise international awareness of how critical women’s empowerment is for security and reconciliation in Afghanistan, the OSCE Secretariat’s Gender Section, together with the Embassy of Afghanistan, organized a visit by the Afghan Minister for Women’s Affairs, Dilbar Nazari, to the OSCE headquarters in Vienna in May 2015. She was accompanied by a delegation of representatives from other government and civil society institutions, including the Director of the Afghan Women’s Network, Hasina Safi – see page 37.

Border Management

The OSCE Border Management Staff College (BMSC) in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, encourages the participation of women in its border security training, which includes gender mainstreaming as part of its core curriculum. The first Afghan women joined the BMSC in 2013; 11 have attended so far. The BMSC also offers courses exclusively for women: a short course for female leaders of border security and management agencies and an all-women staff course, covering topics ranging from management models to information sharing, migration, human trafficking and smuggling, counter-terrorism, anti-corruption measures, conflict management, and leadership.

Customs

The OSCE Centre in Bishkek has conducted specialized training for customs officers from Kyrgyzstan and Afghanistan. One of the achievements of the courses was the participation of seven female Afghan officers. The Centre is determined to encourage more female officers from Afghanistan to take advantage of its train-the-trainer courses so they can share what they have learned during the training with their peers back home.

Economic Empowerment

Economic empowerment of women is an important contributing factor to security and prosperity. The Office of the Co-ordinator of OSCE Economic and Environmental Activities organized a programme for women entrepreneurs from Afghanistan to strengthen their business management skills, improve their professional networks and broaden their market opportunities. They joined counterparts from Tajikistan and Azerbaijan for a one-week training course in Istanbul in 2012. (See story in The OSCE Magazine, Issue 4, 2012.)

Education

The OSCE Academy in Bishkek is a regional centre of post-graduate education and research which runs two MA programmes, in politics and security and in economic governance and development. Students come from across Central Asia and other countries, including students from Afghanistan since 2008. The OSCE Academy in Bishkek has six female graduates from Afghanistan and one current student. The Alumna of the Year in 2015 was a graduate from Afghanistan, Sakina Qasemi. She is now dean of the economics and management faculty at the Gawharshad Institute of Higher Education (GIHE) in Kabul.

Welcome to Security Community

Security Community is the OSCE’s online space for expert analysis and personal perspectives on security issues.

The views expressed in the articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the OSCE and its participating States.